We Need To Talk About Capital Gains Tax

I had not planned to do another blog update until September, wholly based on laziness. During a rare spell of good weather, is it really worth clambering off my summer deck chair to tap out an update on as dry a topic as capital gains tax (CGT)? In usual times CGT never gets a mention but it’s been in the headlines like never before in the run up to this General Election.

The reason I am at the keyboard is that, of the 3% of the UK population that have paid this tax since 2010, I suspect the readership of this blog have 100% paid it or will do so in the near future. All this recent chatter about hiking the CGT rate has probably got you nervous about the outcome of the election and what is likely coming our way. Hopefully this update will help guide your thoughts about how and how hard we are likely to get clobbered.

What’s The Beef?

Our property investment returns are delivered as income through net rents and as a capital gain through an increase in value when sold. Whilst we may fixate on the net rent when we are buying a property (it’s just counting) it is the capital gains which make us all the money in this game. I would go as far as to say that rental income is merely the enabler for the capital increase.

Think of it as being in a casino, you are playing roulette and you bet on just one number, say Black 22. It’s a ballsy move (1 in 37 chance) and one that will require repeated spins of the wheel until eventually you are the winner. Strip any investment down and you are doing just this - guessing the future. The difference with property investing is that whilst you are making a call on a property’s future price, you get your costs covered whilst you wait. Think of your stake money for each spin of the wheel as your mortgage payment and your other property running costs as drinks and snacks at the bar. These costs are covered by the rental payment each month (or each spin). But for the real pay day, you are waiting for your number to come up and in property this is the capital gain when we sell. This is why we need to talk about CGT.

Don’t believe me? Look at your own investments. Look at the equity you have tied up in your properties and think about the return you would get if you just sold up and put it in a deposit account paying say 5%. Now compare that figure to the net income you posted on your last tax return. Unless you have invented another job for yourself by running a high-income HMO or Airbnb-type business, the returns will be similar. To be honest if you have some significant equity built up you may well be much better off just putting it on deposit and sitting on a deckchair 12 months of the year. The only reason then that we put ourselves through all the tenant hassles and boilers packing up etc is the capital gain. With the tax of this primary source of our wealth being under the spotlight now it is well worth us looking at it. It is also worth looking quickly at other likely forms of tax on wealth which could be coming down the tracks with a Labour government.

History

Some think of CGT as a relatively new tax. Tell that to Mary and Joseph who, according to the Bible story, schlepped with their donkey to Bethlehem once a year to fess up to what they owned. Was the donkey tax-deductable? The Bible is unclear on this.

Actually, whilst wealth has been taxed in various forms in the past, CGT is a relatively new tax in the UK. In 1965 it was recognised that clever so-and-so’s were concealing their income as capital gains which went completely un-taxed. The Labour government of the time put an end to this fun and brought in a level of 30% CGT. Following that, there has been a good deal of meddling with it. The guiding principles according to the Treasury for the changes have been:

that the tax be charged on real, rather than inflationary gains.

that the tax should promote long-term investment and entrepreneurship.

and that the tax should not act as an incentive for individuals to avoid income tax, by converting their earnings or profits into capital gains.

These principles are worth remembering as they will guide future changes.

Here are some of the highlights:

1980s - Taper relief introduced to only tax real-terms gains

1999 to 2000: CGT rates partially aligned with rates on savings income

2008 to 2009: Taper relief abolished. Single 18% rate, Entrepreneurs’ Relief replaces Taper Relief and the indexation allowance is withdrawn

2010 to 2011: higher CGT rate of 28% introduced

2016 to 2017: rates reduced to 10% and 20% except for gains on carried interest and residential property

2020 to 2021: the Business Asset Disposal Relief lifetime limit was reduced from £10m to £1m and lifetime gains above £1m were charged at the main CGT rates

2024 - 28% higher rate reduced to 24%.

What Have Labour Got Up Their Socialist Sleeves?

Whilst Labour have insisted that no taxes are going to go up, especially on working people (sorry reader, that’s really not us) we have to assume they have capital gains tax in their sights. The nutters in the party will be baying for it to be equalised with income tax rates ie at the marginal rates of 20%, 40% and 45%. Currently, capital gains on property are paid at 18% and 24% for basic and higher rate payers respectively. Remember, capital gains come as a big chunk so inevitably the higher rates apply - we could be looking at a roughly doubling of the tax overnight. And it will be overnight (not sure which night) as to pre-brief it will allow liquid assets to be disposed of quickly. We will come onto the actions we can take, but do I really think this doubling of tax against our primary source of wealth is going happen? NO.

Here are the options Reeves has:

Do as above, just equalise the rates, keep the nutters happy.

Do as above but re-introduce indexation to allow for inflation over the period the asset is held. More on this here.

Value any paper-gains in wealth for assets held and tax it annually, ie not wait until disposal to trigger the tax. The dreaded wealth tax.

Which do I think is most likely? To answer that, let’s look at the international context and also the history for the tax being paid in the UK.

This excellent graph above (you may need to zoom in) shows by country the income tax rate (start of the arrow) and the capital gains rate (arrow head). Notice any pattern? Apart from plucky Estonia, the arrows all head down so in all countries the rate of capital gains tax is lower than income. That’s normal. Also note that some fairly normal countries have a lower or even zero rate of CGT than UK now. This might seem mad but think about it. Unless you inherit, to be in a position to pay CGT you must first earn some money, you save it and then you buy an asset. To be taxed when you sell it is a double tax. Also, you took risk in guessing if the asset went up - it did not just plop into your account like the wages you needed to buy the asset in the first place. Finally, you may have owned the asset for many years. Any gains may well just reflect the inflation during the period of the hold so it is not a real-terms gain anyhow. The nutters on the left don’t get any of these arguments, but I am sure Reeves does - she plays chess apparently.

So, back to the UK context:

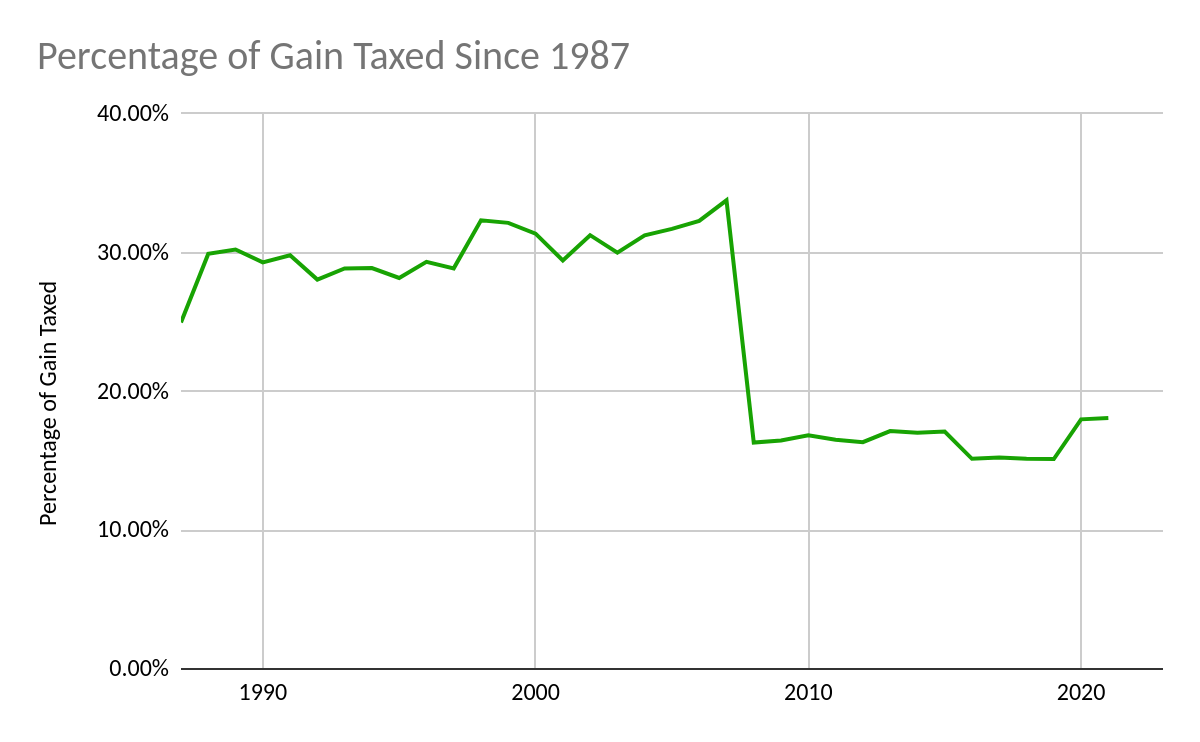

Above we see since 1987 that the amount of gain which was taxed ran around 30% until the various changes cut that in half to around 16-18% ever since. This seems like a good reason to hike the rate paid back up to the levels in the 1990s to increase the amount to the Treasury. But wait….

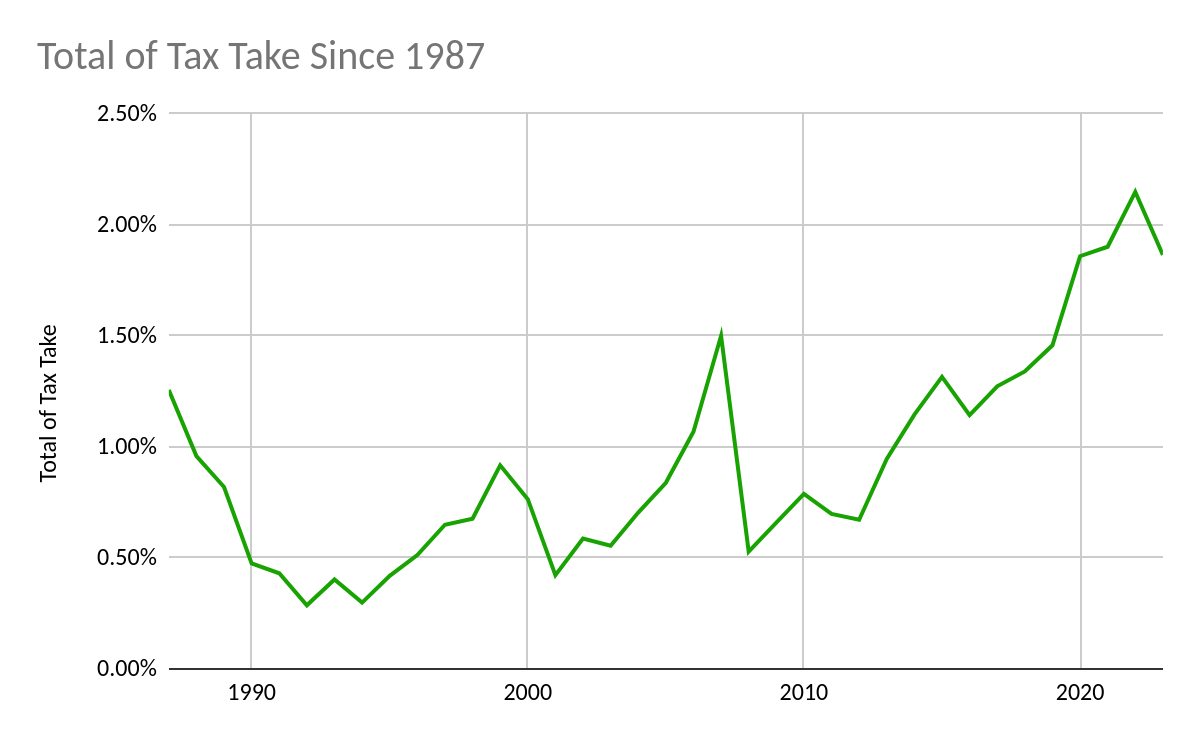

But now look in the above how much CGT represents of the whole tax take over the same period. Once more favourable rates are introduced and things like entrepreneurs relief brought in the amount that CGT of the total tax take roughly doubles, why? Because individuals are less incentivised to come up with clever schemes to avoid paying it and people do not just hold onto an asset scared of the high CGT rate. Some may point out that there has been some amount of concealing income as capital of late but that cannot account for the huge increase in tax take completely. So the logic is that lower rates deliver better returns for the Exchequer - the Laffer curve is real after all.

What Will Reeves Do?

I suspect Reeves would like to keep the rate as it is, clearly it’s currently yielding the most it ever has and any move will undoubtedly decrease the tax take. But she can’t as the nutters will be foaming at the mouth by the time of the autumn statement and positively rabid if left until the spring 2025 budget.

Option 3 above will be appealing to her, but the introduction of an annual wealth tax is fraught with problems. Just how are you meant to calculate it and of course there would be an industry set up to conceal any paper gains. Wealth taxes rarely work, but more on this later. This leaves option 2, raise CGT to the same level as income tax but make allowances for inflation. This will catch those trying to disguise income as capital as the length of their “hold” period is usually very short, typically in-year. It will also encourage long term investment. But remember, Reeves plays chess. She realises, like Gordon Brown did, that when taper relief existed the tax take was very low as CGT is often in reality just a tax on inflation. Her masterly move will be to allow the gains to be tapered down but only to the levels we have today as a maximum (ie 24%). This way she appeases the nutters as the headline rates are inline with income tax and it may even increase the tax take from those who are concealing income.

Checkmate.

What Should We do?

Whichever option Reeves takes, with property being famously illiquid we can do very little to dodge any changes. If option 1 is brought in, we can just stop any sales until it is hopefully reversed. Option 2, with property being a long term investment, is pretty much the status quo. We may even benefit if they are as generous with the taper relief as was the case in the 1980s and 1990s. If she goes for Option 3, the annual wealth tax, this will take many years to implement so some careful disposals before it is fully in place may be possible.

In sum, even with all this noise about CGT currently, these is little we should or could do and in all probability will not affect us much anyway.

Other Forms of Wealth tax

Here’s actually where it could be less calm. The above regarding CGT is fairly straightforward but now I will move into pure guessing territory as we look at the other forms of wealth which could be taxed under Labour. Students of Fred Harrison (the chap who made the 18-year property cycle famous) will know that this is a prime time politically to implement a Land Value Tax. In its purest form, this is an annual tax on the unimproved value of all land which in time fully replaces any tax on income. I would love to be proved wrong but this is certainly too radical for Keir Starmer. Instead they will be doing a lot of faffing about with all the current wealth taxes - stamp duty, council tax inheritance tax and pensions. Let’s have a good old guess at what is most likely.

First, a quick quiz. Which property below has the more expensive Council Tax Bill?

No, it’s not a trick question. Obviously it is the semi in Redcar, a whole £100 more per year than the King’s house. It would seem that the council tax regime, based on property values in 1991, needs a bit of a tweak.

What will Labour do? Who knows, but this is one they may take time to tackle as it is huge. Their instincts may be to abolish the hated tax of stamp duty and roll it up with council tax. Think about it. The Average council tax bill is £2171 and average house price around £280,000 so just under 1% of the house value per year. Stamp duty could be phased out and rolled into a 1-2% annual tax on value of a property as priced at last transaction, indexed via the land registry for that area. This would remove the friction of stamp duty in the property market and smooth the tax income to the Treasury. With property values higher in London and the South East, it would also encourage mobility and to a degree help with the levelling-up agenda. The tax would likely be made the liability of the property owner. In other words, tenants will not be liable and the bill will over time be incorporated into gross rents charged. How likely is this massive change? Who knows, but the system described above is pretty much how many countries like the USA operate now so it is not entirely left-field.

Finally on the other forms of wealth tax. Inheritance tax is a no-brainer for Labour to go at. It’s a tax of dead people who don’t have much of a say in the matter, rich dead people at that. You guess that they will not be too draconian on the level it starts at and allow family homes of a reasonable size to pass down with little or no tax. It is the schemes that avoid the tax altogether such as the passing down of farmland that will be under the microscope.

And lastly, savings into pensions and ISAs. This area is so generous at the moment and must get trimmed back in some way. At the moment it is possible for you to salt away £60,000 each year into a pension and attract tax relief up to 45% on the full amount. You can also stuff £20,000 each year into an ISA and depending on your children’s ages (and depending if you have children) gift them £9,000 a year into an ISA or if they are over 18 top up their LISA £4,000 per year. Whilst the various ISAs are topped up from after-tax income, they grow tax-free for their lifetime. This is all very generous compared to other countries and must be in the cross-hairs of any self-respecting incoming socialist government.

On these various forms of taxes, again there is little that can be done now to mitigate any potential changes. It would be prudent to stuff any ISAs and SIPPs as much as you are able this year. In particular, you are able to go 4 years back with SIPPs so if you have not fully contributed over the last 4 year period then you could do so now. But other than that bit of house-keeping I would say let it all pass over, enjoy the summer and get back to the deckchair. Exactly what I will do now.